Habermas Machine

This post is a distillation of a recent work in AI-assisted human coordination from Google DeepMind.

The paper has received some press attention, and anecdotally, it has become the de-facto example that people bring up of AI used to improve group discussions.

Since this work represents a particular perspective/bet on how advanced AI could help improve human coordination, the following explainer is to bring anyone curious up to date. I’ll be referencing both the published paper as well as the supplementary materials.

Summary

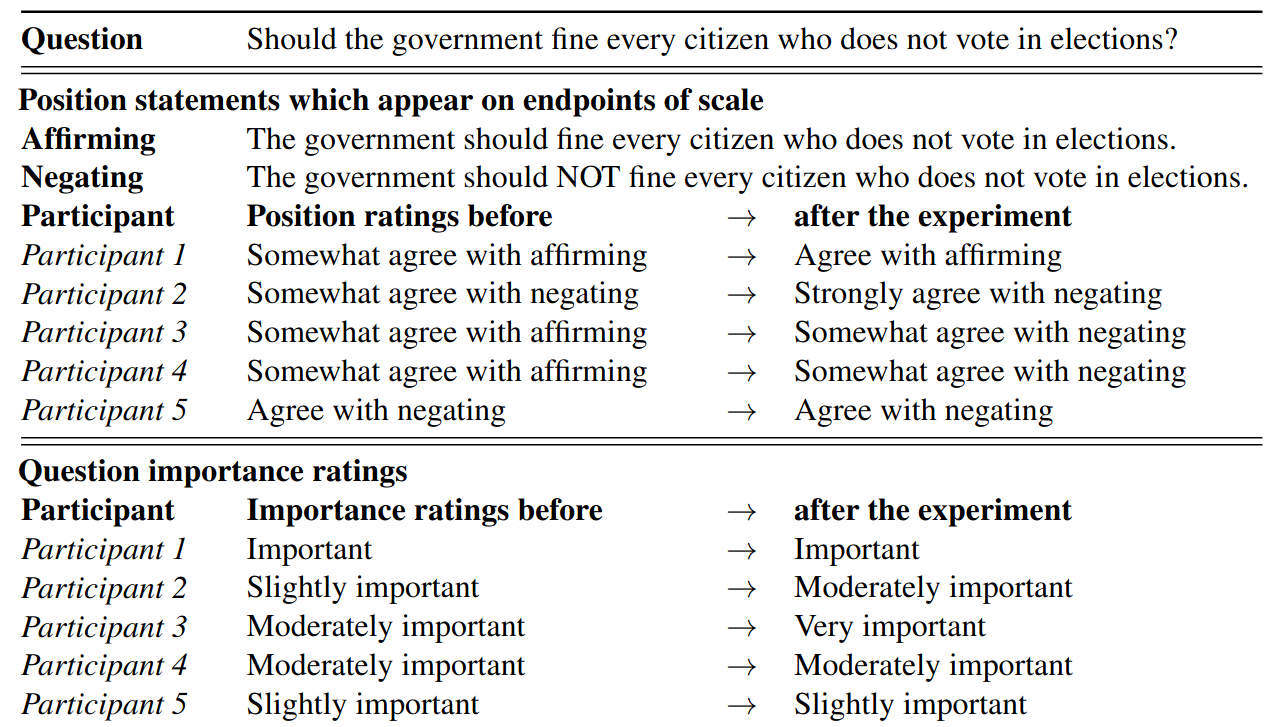

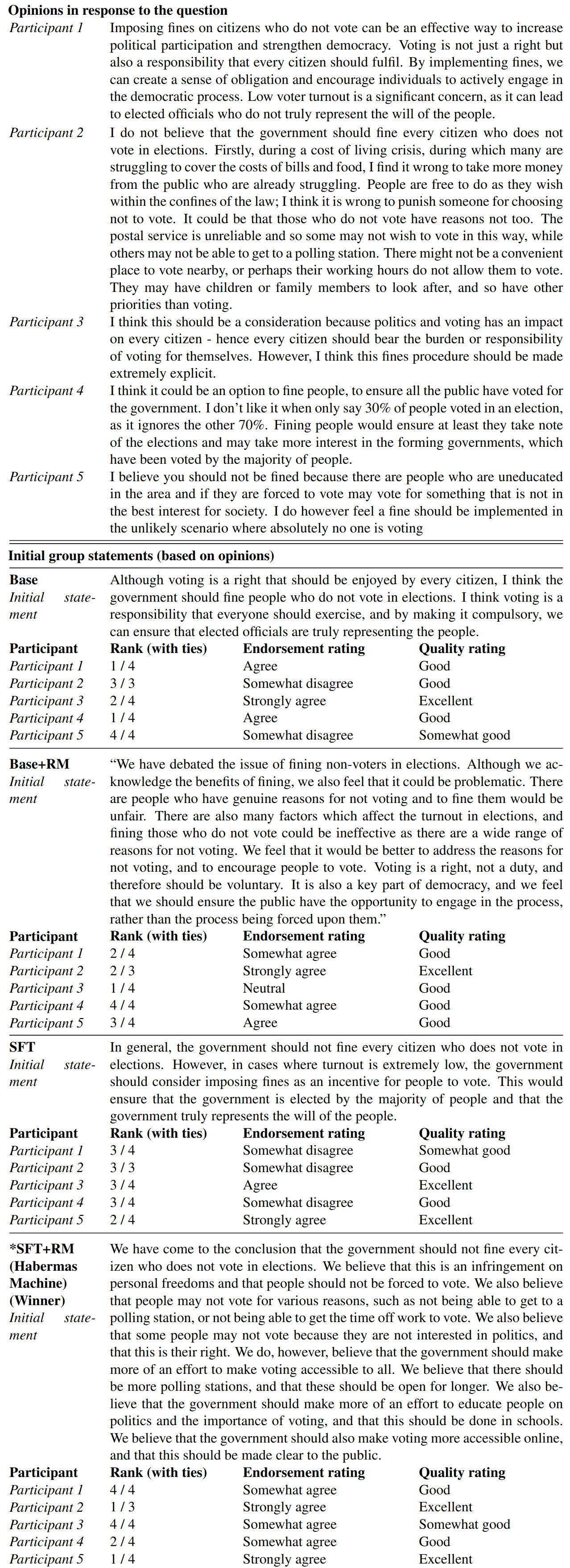

The Habermas Machine1 (HM) is a scaffolded pair of LLMs designed to find consensus among people who disagree, and help them converge to a common point of view. Human participants are asked to give their opinions in response to a binary question (E.g. “Should voting be compulsory?”). Participants give their level of agreement2, as well as write a short 3-10 sentence opinion statement representing their view on the issue.

The system takes the individual statements of opinion from different people and outputs a single “group statement,” optimized for broad endorsement. During a session, the system refines its output iteratively, incorporating live human feedback to help it converge on a widely acceptable perspective.

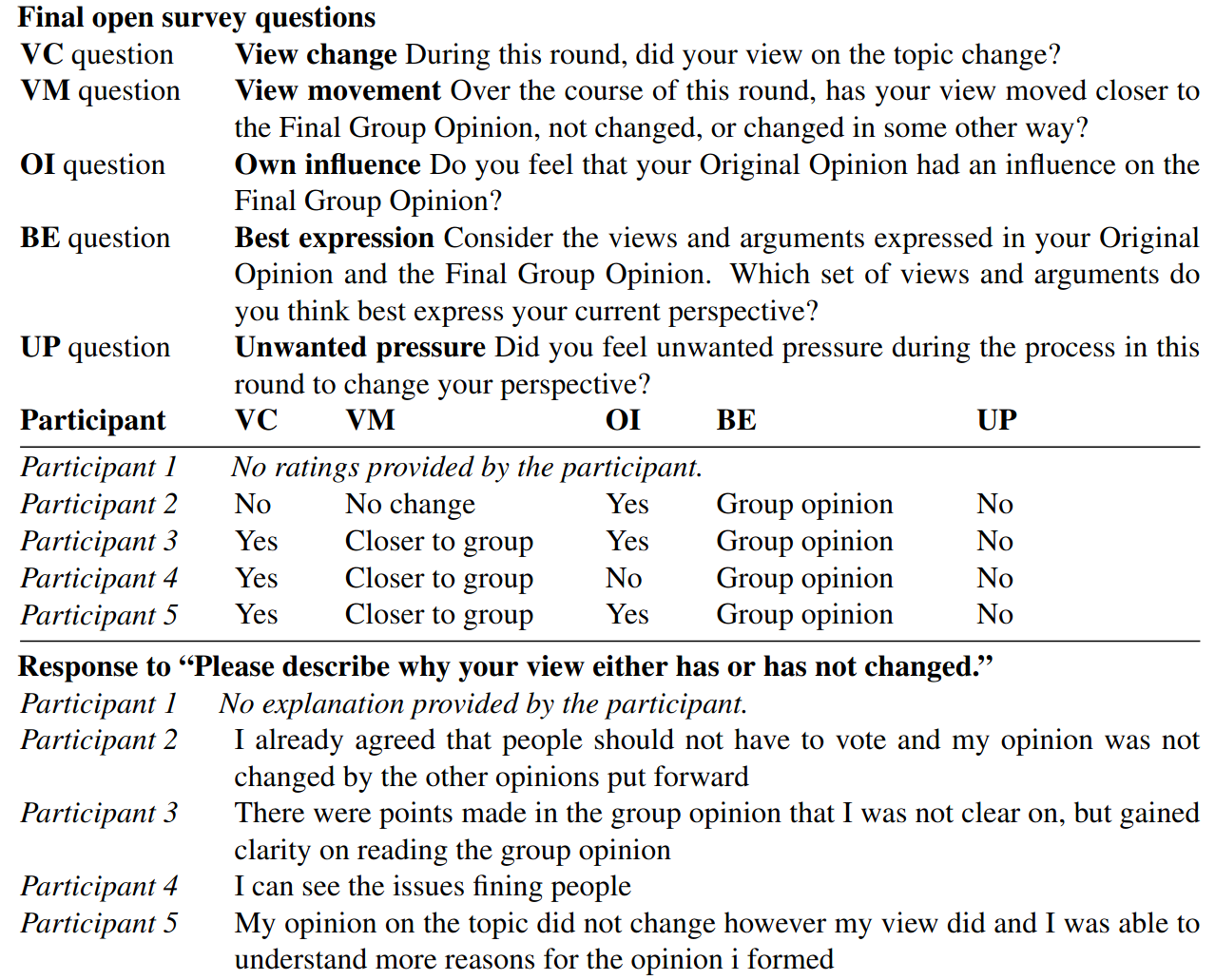

At the end of the session, participants are asked if their position on the question changed, to assess if the group moved toward consensus.

Full Process

The method starts with a question and ends with a statement presenting the group’s position on the question. Some of the steps in the process are automated, while others are performed by the human participants. The HM plays the role of mediator, producing group statements which synthesize the perspectives of all the participants. This happens in two places:

- Initial Phase: After seeing the question, participants are each asked to write their opinions. The HM takes these initial opinions and synthesizes them into a group statement. This is repeated to produce 4 different options, which the participants narrow down to a single statement via an election.3

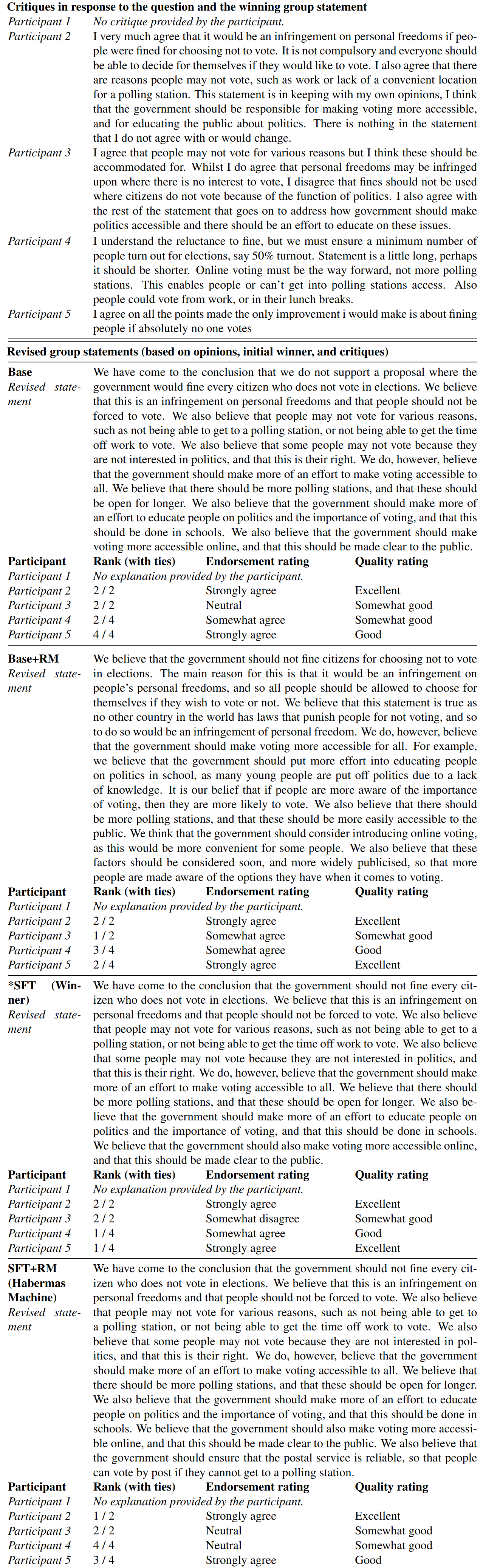

- Critique Phase: After seeing the winning group statement, participants are asked to give critiques. The HM takes these critiques and uses them to propose revised group statements, which the participants are again asked to vote on.

This process ends with the participants selecting one group statement as their final choice. The participants are then also asked to reconsider their initial stance on the question, to evaluate whether they changed their minds or if a group consensus emerged.

Automated Mediation

The HM itself consists of two finetuned Chinchilla models, which are used to generate a series of candidate group statements and narrow them down to a single group statement via a simulated election.

- Generative model (70B)

- Reward model (1.4B)

The machine produces a group statement by taking the following steps:

- Generation: The generative model is prompted with the original question and the opinions provided by 5 human participants.4 This is used to independently sample 16 candidate group statements.

- Prediction: The reward model is then used to predict how each person will rank the candidate group statements. The reward model is prompted with the question, a specific person’s opinion, and one of the candidate group statements. The model then outputs a score estimating how likely the person would rank that statement above the others.

- Simulated Election: The predicted rankings of candidate group statements are then used to run a simulated election, resulting in a single winning group statement.

The winner of the simulated election is the machine’s final output.

Empirical Results

The authors test their system by running live sessions with thousands of participants, all residents of the UK. The original research does a lot of different empirical evaluations of their system, which I omit for the sake of brevity. Here are some quick takeaways:

First, AI mediation does cause people to change their mind on the original question, and converge toward group consensus (people explicitly admit to their view changing). This does not happen without mediation (opinion exposure cohort).

Second, they show that the HM slightly outperforms human mediators, at least at writing statements that participants prefer. It performs about the same as human mediators at causing an increase in group agreement. It is important to note, however, that these were untrained mediators, sampled from the same pool of people selected as participants.

Comparison to Gemini 1.5 Pro

Not included in the final paper (just the supplemental materials).

The authors also performed an evaluation of Gemini 1.5 Pro’s abilities, which seemed noteworthy.

The authors try to evaluate the effect of using a state of the art Gemini model, but by just prompting it and doing no finetuning. They compare how well both Gemini and the 1.4B reward model are able to predict human rankings, and they find that Gemini significantly underperforms the reward model.

Gemini is prompted with the question and a person’s initial opinion, and is then used to rank candidate group statements in two different ways:

- Comparing the average log probability of tokens in each candidate group statement (ranking them from highest to lowest average probability)5.

- Giving all candidates to the model and asking explicitly for a ranking.

This is done to predict individual rankings as well as aggregate rankings (by running a simulated election with individual rankings). In all cases Gemini does better than chance, but it always performs significantly worse than the finetuned reward model. I personally found this surprising, given the large difference in scale between the models.

Embedding Space Analysis

Finally, the authors also look for bias in group statements by examining the semantic embeddings of both the human opinions and generated outputs.

First, they identify a “position component” in the semantic embedding space which separates the affirming and negating answers to the original question (e.g. comparing the embeddings of “Voting should be compulsory” and “Voting should not be compulsory”).

They then show that group statements usually fall in between the opinion statements they were based on, suggesting that they tend to be a compromise between positions.

They also examine the balance between the majority and minority clusters (partitioning the participants by their initial level of agreement with the question). They find no evidence, from comparing the embeddings, that the HM has any preference for the majority.

This kind of analysis is pretty ad hoc, but finding ways to demonstrate neutrality seems pretty important if a system like this were ever to be deployed in high stakes, or low trust contexts. Furthermore, as LLMs get better at mediating, there might be bigger concerns about adversarial persuasion and manipulation of participants toward one position or the other.

Training Details

Both the generative model and the reward model are finetuned from base models. The training data they used for finetuning is publicly available on Github.

Generative Model

The generative model is finetuned in 3 iterations on human-curated samples of its own generations. Each iteration uses fresh human participants, but top statements are also included from previous iterations. Model-generated statements are filtered according to human provided quality scores (>5 average on a 7 point scale), but it’s not clear from the paper what fraction of statements make the cut.

Each iteration trains on roughly 5000 samples, running multiple epochs until a validation set shows signs of overfitting. The same model was trained to do both phases of the deliberation process (initial and critique phases).

Reward Model

For each set of human opinions, the generative model produces 4 candidate group statements which are then ranked by the participants, and the reward model is then trained to predict these rankings. The real human rankings are first converted into pairwise preferences, and the reward model is trained to fit a Bradley-Terry preference model, estimating a score for each statement proportional to how likely it is to be preferred.

A linear layer is added on top of the 1.4B base model which outputs a scalar value. The model learns to compute this value from seeing a prompt including the question, the initial opinion response, and a single candidate group statement.

Example Session

The following is an example run of the deliberation process, taken from the supplementary materials. This session has been modified to compare 4 different ways to generate a group statement:

- SFT+RM: This is the full HM, using both a model with supervised finetuning (SFT) and a reward model guided simulated election (RM).

- SFT: This uses supervised finetuning, but no simulated election.

- Base+RM: This uses a simulated election, but uses the original base model without finetuning.

- Base: This generates a group statement by just prompting the base model.

Normally all 4 statements would be generated by the full HM, but this case lets us qualitatively compare what both finetuning and simulated elections are contributing to the statements.

Question and Summary

The group evaluates the question of compulsory voting, and converges toward the position that the government should not fine citizens who don't vote. Participant 1 still dissents with the majority opinion at the end.

Initial Phase

Participants submit their opinions, and a group statement is chosen. In this case the HM (SFT + RM) produces the winning statement. The statement, while acknowledging the possible benefits of compulsory voting, seems to side primarily against it. Curiously, rather than just summarizing the human opinions, the HM offers a novel compromise position (not brought up by any of the participants), that the government should invest in non-coercive methods of increasing turnout instead.

Critique Phase

Participants submit their critiques of the winning group opinion, and a new revised group opinion is chosen. In this case the finetuned model which doesn't use a simulated election (SFT) produces the winning statement. The refined statements are all very similar to the winning statement from the previous phase, changing only minor details. Participant 1 has also stopped participating for some reason.

Final Survey

Four out of the five participants converged to the position that the government should NOT fine people for failing to vote. Participants also give some more detail about how their view changed.

Conclusion

Hopefully this quick overview at least gives a rough sense of what they’ve done, and maybe some clues about where a method like this might go in the future. While this work is focused primarily on helping people to find common ground on a variety of UK-relevant social issues, this research could develop in a lot of different directions. Future versions of this kind of AI-mediated dialogue could potentially have a place in improving negotiations, resolving intellectual disagreements between researchers, or accelerating public consensus around AI policy questions.

This work uses an LLM which is fairly rudimentary (by 2025 standards), and so it seems likely that future models with improved reasoning abilities could be used to play a much bigger role in improving collective dialogue, depending in large part on the order in which the relevant capabilities emerge.

Footnotes

-

The Habermas Machine is named after Jürgen Habermas. ↩

-

Participants are asked if they agree with either the affirming or negating rephrasing of the question (“Voting should be compulsory” vs “Voting should not be compulsory”). This question is asked both before and after deliberating, to assess whether they changed their minds during the process, and if the group converged toward a shared opinion. ↩

-

All elections in the paper, simulated or real, use the Schulze voting rule. This method was chosen because of 1) independence of “clones” and 2) robustness to strategic voting. ↩

-

The number of participants is usually 5, but the system is also trained to be robust to smaller groups. ↩

-

This is meant to be a proxy for evaluating Gemini as a generator model. This is a pretty strange method, and I'm personally not surprised that it failed to work. ↩